hell came to michigan

HORROR AND HAUNTINGS OF THE BATH SCHOOL MASSACRE

There are two things in life that are certain: death and taxes. In the case of the horror that befell a Michigan town one spring morning in 1927, it was a deranged man’s fury over taxes that resulted in the deaths of 45 people.

On May 18, 1927, hell came to the village of Bath, Michigan.

The community was forever changed when a bomb went off in the basement of the local consolidated school, followed by a car bomb blast. The explosions killed 38 school children, two teachers, four other adults and the bomber himself. The deaths still constitute the deadliest act of mass murder in a school in American history.

The perpetrator was a farmer named Andrew P. Kehoe who was upset over a property tax that had been levied to build the consolidated school. He ran for and was elected to the board of education, where he tried unsuccessfully to get the school portion of his property taxes reduced. Soon the higher taxes, coupled with his wife’s medical expenses, caused him to lose his farm. It was too much for Kehoe to take and he started plotting revenge.

With the recent concern over school violence in our country, we yearn for “the old days,” when small-town life was peaceful and schoolchildren were safe from harm. The story of the Bath School Massacre serves as a bitter reminder that the good old days were not always good.

Andrew Kehoe and his wife, Nellie

Andrew Kehoe was born in Tecumseh, Michigan, on February 1, 1872. One of 13 children, he had a troubled life. His mother passed away when he was very young and while his father later remarried, Kehoe and his stepmother never got along. One day, when Kehoe was 14, his stepmother attempted to light an oil stove in the kitchen. The stove exploded and set her on fire. Kehoe simply stood and watched her burn. After a few minutes, he doused her with a bucket of water, which put out the fire. Gravely injured, she later died. It would later be speculated that Kehoe had something to do with the malfunction of the stove.

He attended Tecumseh High School and went on to Michigan State College in East Lansing, where he met his future wife, Nellie Price. He later moved out West for a few years and spent some time in St. Louis, where he suffered a severe head injury as the result of a fall in 1911. He was attending electrical school at the time of the accident. Kehoe was in a coma for two months. Whether this injury contributed to Kehoe’s madness will never be known, but it certainly seems possible. His behavior became more and more erratic after the fall, even though he physically recovered.

When Kehoe returned to Michigan, he married Nellie. She came from a rather wealthy family, which owned several pieces of property in Clinton Township. Eventually, Andrew and Nellie bought 185 acres from an uncle’s estate. The property was located just outside of the unincorporated village of Bath. Kehoe quickly gained a reputation for his intelligence, cleanliness and rather odd behavior. He was quick to help people, but equally quick to be critical when he didn’t get his own way. He was intelligent able to easily articulate his views, but had little patience for ideas that did not agree with his own. He was habitually neat and often changed his shirt twice a day. He liked to tinker with machinery, especially with electrical gadgets. He seemed happiest when repairing or adjusting the machinery on his farm. New ways of carrying out familiar chores intrigued him and he was constantly looking for ways to improve the farm. But there were troubling reports from some of his neighbors that Kehoe was cruel to his farm animals and once beat a horse to death.

Kehoe also gained a reputation for being tight with a dollar, a trait that helped him get elected to the school board in 1926. On the board, Kehoe constantly campaigned for lower taxes because he claimed the current taxes were causing him financial hardship. His creditors tried to work out a payment plan with him, but were unsuccessful. Soon, he stopped paying his mortgage and homeowner’s insurance premiums. To complicate matters, Nellie Kehoe was chronically ill with tuberculosis. She required frequent hospital stays, which wiped out what little savings they had left. Kehoe was sure that they would lose the farm and plunge even deeper into debt. In his mind, high property taxes were the source of all his financial woes. He saw nothing good come from the taxes and believed that many of the town’s expenditures were wasteful and pointless.

But above all, without any valid reason, he blamed the five-year-old Bath Consolidated School for his troubles.

Throughout the country during this era, most of the one-room schools, where different grades shared the same classroom and teacher, were starting to close down. There was beginning to be a widespread belief that children would receive a better education if all the students from a region could instead be educated at a single facility, with the students divided by age into grades. After years of debate and planning, the local district built a new school called the Bath Consolidated School. A school tax was levied to pay for the project and as a result, property owners like Andrew Kehoe had to pay.

Kehoe argued against the new school and complained constantly about the increase in taxes, stating that they were illegal and unfair. He considered at least one of his fellow school board members to be his bitter enemy – board president Emory E. Huyck. Kehoe claimed that Huyck was influencing the other members of the board to vote for higher taxes. Kehoe became obsessed with school board politics, Emory Huyck and the injustice of property taxes, which he believed were ruining his life.

Bath Consolidated School, which Kehoe inexplicably blamed for all of his financial troubles.

No one knows for sure when Kehoe conceived the idea for the bombing, but based on the activity at the school and the purchase of explosives, his plan had probably been underway for at least a year. He probably started working things out in the winter of 1926, when the board asked him to perform maintenance inside the school building. Regarded as a talented handyman, he was known to be especially good at installing electrical wiring. As a board member appointed to conduct repairs, he had free access to the building and his presence was never questioned.

At some point that summer, Kehoe began purchasing large quantities of pyrotol, an incendiary explosive that was first used during World War I. Farmers often used it for excavation, so Kehoe’s purchases of small amounts of the surplus explosive at different stores on different dates did not raise any suspicions. Neighbors reported hearing explosions on Kehoe’s farm, which he explained by saying he was removing tree stumps. No one thought this was odd and no one questioned it when he drove to Lansing in November 1926 and bought two boxes of dynamite at a sporting goods store.

Throughout the spring of 1927, Kehoe began to transport the pyrotol into Bath School. He did so in small increments and no one noticed anything out of the ordinary. He calculated exactly what he needed each day and brought just that amount. He had volunteered to fix the wiring in the school’s basement but instead of repairing things, he wired the explosives throughout the basement, connecting various charges of explosives beneath the floors and in the basement rafters. He slithered into the sub-floors and crawlspaces beneath the school, hiding large amounts of pyrotol behind pipes and beams. Over time, he managed to run thousands of feet of wire throughout the building – all under the feet of unsuspecting children and teachers.

The horrific project was completed in early May. Kehoe set the charges and waited. During this time, he also wired his home in the same manner. In every structure on the farm, he rigged a series of firebombs – crude devices made from containers filled with gasoline and wired with automobile spark plugs attached to a car battery.

On May 17, he drove his car over to the front of his barn and loaded the back seat with metal debris. He threw in nails, old tools, pieces of farm machinery and anything else capable of creating shrapnel in an explosion. When the back seat was filled with bits and pieces of metal, Kehoe packed dozens of wrapped sticks of dynamite under the front seat and placed a loaded rifle on the passenger’s seat next to him.

(Above) The Kehoe farmhouse before it was set on fire.

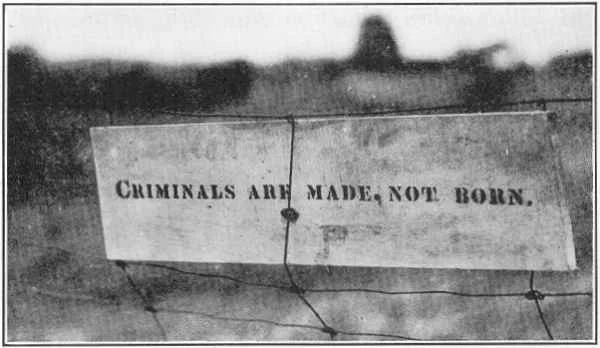

(Below) A sign that Kehoe left in the fence at the farm, discovered by investigators after the explosion.

After he completed this grim task, he set out on another, bloodier one. Records at Lansing’s St. Lawrence Hospital revealed that Nellie Kehoe had been discharged on May 16. On the afternoon of the following day, Kehoe killed his wife by hitting her over the head with a blunt object. The exact nature of the object was never determined, because the ever-thorough Kehoe burned his house, barn and outbuildings to the ground. After killing his wife, Kehoe dumped her body into a wheelbarrow and pushed it over to the back of the chicken coop. Piled around her on the cart were silverware, jewelry and a metal cash box containing the ashes of burned bank notes. After abandoning his wife’s body, Kehoe completed wiring the farm to explode. He had placed one of his homemade firebombs in every building and if all went according to plan, his property would simultaneously explode and burn to the ground before help could arrive. The house, barn, outbuildings and even the farm animals that had been tied in their enclosures would be destroyed. There would be nothing left for the bank to foreclose on.

On the morning of May 18, the children began arriving at the consolidated school at about 8:00 a.m. To the students, it was a day like any other. They laughed and talked, pushed and shoved in the hallways and hurried to their classrooms. They had no way of knowing that – just inches beneath their feet – more than 1,000 pounds of explosives waited for an electrical current that would start a chain reaction that would change their lives forever.

At approximately 8:45 a.m., two miles from the school, Kehoe detonated the firebombs on the farm. The place exploded into flames, sending smoke, fire and debris into the air. Burning streamers of flame fell from the sky, raining down on the farm across the road. The neighbors, hearing the explosion, ran to Kehoe’s farm to offer assistance but as they hurried down the driveway, Kehoe was already behind the wheel of his car. He calmly looked at them through the open window and said, “Boys, you are my friends. You better get out of here. You better go down to the school.” Kehoe roared away, leaving his confused neighbors and a farm completely engulfed in flames, behind him.

As Kehoe drove away, another tremendous explosion, much larger than the first, was heard in the distance. The sound, it was later said, was heard for 10 miles in every direction. The Bath Consolidated School had been blown up. O.H. Buck, who had run to the Kehoe farm after the first series of blasts, heard the massive explosion of the school. He later told reporters, “I began to feel as if the world was coming to an end.”

And for many, it was.

The remains of Kehoe’s car, which he had also caused to explode outside of the school.

Before the dust from the explosion had settled, townspeople were already digging through the rubble of the school. The sound of children screaming and moaning could be heard coming from the ruins. Fully half the building, the northwest wing, was gone. The walls were destroyed and the roof lay on the ground. Bodies of children could be seen protruding from the bricks and stone, little arms and legs only partially visible. Faces covered with blood and dust peered through the broken windows and from between splintered beams of wood. Frantic mothers ran screaming to the scene, for almost every family in town had at least one child enrolled at the school. The sobbing of trapped children could be heard as some of the mothers fought with rescuers to pull their children from the wreckage. Men worked feverishly in the mountain of rubble, tossing aside bricks and pushing twisted metal as they searched for survivors.

Monty Ellsworth, a neighbor of the Kehoe, recounted, “There was a pile of children of about five or six under the roof and some of them had arms sticking out, some had legs, and some just their heads sticking out. They were unrecognizable because they were covered with dust, plaster, and blood. There were not enough of us to move the roof.” Ellsworth volunteered to drive back to his farm and retrieve the heavy rope that was needed to pull the structure off the children’s bodies. On his way back to the farm, Ellsworth reported seeing a cheery-looking Kehoe driving into town toward the school. Ellsworth said, “He grinned and waved his hand; when he grinned, I could see both rows of his teeth.”

Less than 30 minutes after the explosion, Kehoe arrived on the scene. No one knew that his car had been loaded with dynamite and metal debris. He got out of his car and saw his nemesis, board president Emory Huyck. Kehoe waved and called him over to the car. As he approached, Kehoe picked up the rifle from the seat next to him, aimed it at the dynamite and fired. Another terrible explosion rocked the town. A huge ball of flame shot upwards and shrapnel was sent flying in every direction, ripping apart trees, splintering houses, shattering windows and cutting down everything in its path. Emory Huyck and town postmaster Glen Smith were instantly killed. Kehoe was almost totally obliterated. An eight-year-old student named Cleo Clayton, still dazed from the first blast, was walking along the street when the second explosion occurred. He was struck in the stomach by a large piece of metal from the blast. He died a few hours later.

The people working at the rubble of the school were panicked and confused. No one understood what had happened, most imagining that they were under some sort of military attack. Rumors swept through the crowd about more explosions to come. In the distance, Kehoe’s farm was still burning, sending a column of black smoke high into the air. Smaller explosions could still be heard from the farm as Kehoe’s leftover pyrotol continued to explode. Across the street from the school, trees, houses and parked cars were on fire from the original blast. Pieces of bodies were strewn on the grass and in the bushes and many people had fainted or had become hysterical. Over 100 people had been injured and more injuries were being found every minute. At that point, no one had any idea just how many had been killed.

Minutes after Kehoe’s car exploded, the Lansing fire and police departments arrived on the scene. They were followed by the Michigan State Police and representatives of the state department of public safety, but nothing could have prepared these hardened veterans for what they saw: wrecked and burning cars, downed trees, a collapsed school building that was filled with screaming children, fires everywhere. It was like a battle scene from some distant war – or a taste of hell.

Local physician Dr. J.A. Crum and his wife, a nurse, had both served in World War I, and had returned to Bath to open a pharmacy. After the explosion the Crums turned their drugstore into a triage center. Private citizens were enlisted to use their automobiles as additional ambulances to take survivors and family members to area hospitals.

A short distance away from Kehoe’s destroyed car, Mrs. Frank Smith stood in front of her home watching in horror as the events took place before her eyes. In the corner of her garden, amidst the flowers and shrubs, she saw a crumpled mass of bloody clothing. As she looked closer, she saw that it was part of a human body, mangled almost beyond recognition. Protruding from a rear pocket of the clothing, she saw some papers and carefully removed them. When she looked over the papers, she saw that part of it was a bankbook from the Lilley State Bank of Tecumseh. Andrew Kehoe’s name was on it. Mrs. Smith ran over to a police officer who was directing rescue efforts at the school, and he brought over some of Kehoe’s neighbors to view the body. A positive identification was made. They finally understood Kehoe’s odd words to them as he drove away from his burning farm. He had urged them to go to the school. They could have never imagined what he had planned there.

Hundreds of people climbed through the wreckage to and rescue the children pinned underneath. The injured and dying were transported to Sparrow Hospital and St. Lawrence Hospital in Lansing. Michigan Governor Fred Green arrived during the afternoon of the disaster and assisted in the relief work, carting bricks away from the scene. The Lawrence Baking Company of Lansing sent a truck filled with pies and sandwiches, which were served to rescuers in the township's community hall.

The unexploded dynamite that was found inside of the school after the initial blast. If it had gone off, there may have been no survivors of the massacre.

As policeman, firefighters and volunteers searched through the rubble, desperately looking for survivors, a chilling discovery was made in the ruined basement: a huge cache of unexploded dynamite. State Police officers who emerged from the basement of the school with a bushel basket filled with dynamite informed everyone that there was even more still inside, still attached to a battery and a clock. The rescue efforts suddenly came to a halt as the area around the school was cleared. Working frantically in the broken beams and shattered concrete, fearing they could be blown up at any moment, police officers carefully dismantled what remained of Kehoe’s mad plan. They carried out 504 pounds of dynamite, along with wires and detonating devices. The pyrotol had been divided up into eight different bombs which were hidden in various spots on the south end of the school. Experts later theorized that the first blast had caused some sort of short circuit, which made the additional bombs malfunction. If the rest of the dynamite had gone off, the school would have been completely demolished and the death toll would have surely been in the hundreds.

Slowly, the bodies of the dead were carried out of the ruins of the Bath Consolidated School. They were placed in neat rows on the scorched grass and hastily covered up. A short distance from this grim scene, Mrs. Eugene Hart sat in the street, with her two little dead girls, one in each arm, and her son lying dead in her lap. One of the police officers at the scene later told newspapers, “There were sights that I hope no one will ever have to look at again.”

The bodies of the children were taken one by one to the township hall, which served as a temporary morgue. Dazed parents were brought in to identify the remains of children, some of whom were horribly burned and disfigured by the blast.

The ruins of the Bath Consolidated School after the explosion. This horrific event is the worst school massacre in American history.

The following day, police and fire officials gathered at the Kehoe farm to investigate the fires. On May 19, the body of Nellie Kehoe was found. Her body was so disfigured that she first went unnoticed by everyone who walked past her. She had been burned almost beyond recognition. Her left arm and her right leg were both missing. Only the axle and wheels remained of the cart on which her corpse had been placed. All of the Kehoe farm building had been destroyed and all of the animals that had been trapped in the barns were dead. The amount of unused equipment and materials on the property reportedly could have easily paid off the mortgage – but Kehoe had been too obsessed with the “unfair” taxes for him to realize it.

As officials searched the property for clues to the devastation, they found a hand-lettered wooden sign that Kehoe had wired to a fence that bore the short message that he likely imagined would explain his actions: “Criminals are made, not born.”

All over the world, newspaper headlines announced the shocking tragedy in Bath. The press struggled to find reasons for Kehoe’s rampage, but of course, there were none. The Bath community was devastated and the loss could not be measured in simply the number of children that had been killed. There was no one in the community that had not been touched by the tragedy. Everyone had lost a relative, a friend, a classmate or a teacher. In addition to the human toll, Bath faced financial catastrophe. A new school would have to be built. The future now looked bleak.

The American Red Cross, which set up operations at the Crum pharmacy, did what it could to provide aid and comfort for the victims. The Lansing Red Cross headquarters stayed open until 11:30 on the night of the disaster to answer telephone calls, update the list of the dead and injured and provide information. The Red Cross also managed donations that were sent to pay for both the medical expenses of the injured and the burial costs of the dead.

Over the next few days, there was an endless wave of funerals in Bath, with 18 of them being held on Saturday, May 22. The last funeral was held on Sunday, May 23, the same day that Charles Lindbergh completed the first solo transatlantic flight to Paris. This event shared newspaper space with news of the tragedy in Michigan. Over 100, 000 automobiles passed through Bath that weekend, a staggering amount of traffic for the small village. Some Bath citizens regarded this armada as an unwarranted intrusion into their time of grief, but most accepted it as a show of sympathy and support from surrounding communities. Unfortunately, as with any other tragedy, heartless curiosity-seekers also made their way to town, as did the headline-seekers like the Ku Klux Klan, who proclaimed that the actions of Kehoe, a Roman Catholic, were the result of his adherence to the stance of the Catholic Church against what they considered “Protestant or godless schools.”

A coroner’s inquest was held the following week. The coroner had arrived at Bath on the day of the disaster and had sworn in six community leaders to serve as the investigative jury. The Clinton County prosecutor conducted the examination and dozens of Bath citizens and law enforcement personnel testified before the jury. Although there was never a doubt that Andrew Kehoe had carried out the bombing, the jury was asked to determine if the school board or any of its employees were guilty of criminal negligence.

The testimony lasted for more than a week and in the end, the jury exonerated the school board and its employees. In the verdict, the jury concluded that Kehoe “conducted himself sanely and so concealed his operations that there was no cause to suspect any of his actions; and we further find that the school board, and Frank Smith, janitor of the school building, were not negligent in and about their duties, and were not guilty of any negligence in not discovering Kehoe's plan.”

It was determined that Kehoe had murdered Emory Huyck on the morning of May 18. They also found that the school was destroyed as part of a plan that was carried out by Kehoe alone, without the aid of conspirators, and that he had willfully caused the death of 44 people, including his wife, Nellie. On August 22, some three months after the bombing, fourth-grader Beatrice Gibbs died following hip surgery. It was the final death attributed to the Bath School Massacre.

The jury returned a judgment of suicide as the cause of Andrew Kehoe’s death. His body was eventually claimed by his sister. Without any ceremony, he was buried in an unmarked grave in an initially unnamed cemetery. Later, it was revealed that Kehoe was buried in the pauper’s section of Mount Rest Cemetery in St. Johns, Michigan. Nellie Kehoe was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Lansing by her family. Her tombstone bears her maiden name of Price.

The people of Bath were left with no other choice but to move on. Governor Fred Green created the Bath Relief Fund with the money supplied by donors, the state and local governments. Scores of people from all over the country donated to the fund, which eventually allowed for the demolition of the damaged portion of the school and the construction of a new wing with the donated funds.

School resumed on September 5, 1927, and for the first school year, classes were held in the community hall, the township hall and two retail buildings. Most of the students returned. An architect from Lansing, Warren Holmes, donated plans for a new school and the school board approved contracts for a new building on September 14. On September 15, Michigan’s Republican U.S. Senator James J. Couzens presented a personal check for $75,000 to the Bath construction fund and the school’s new wing was named in his honor.

In 1928, artist Carlton W. Angell presented the board with a statue called “Girl with a Cat”. The statute currently rests in the Bath School Museum, which is located in the school district’s middle school, adjacent to the bombing site. Angell’s inscription on the piece stated that it was dedicated to the courage and determination of the people of Bath. The sculpture was funded by donated pennies from students all over Michigan. According to legend, the pennies were melted down and used to cast the statue.

In 1975, the new school was also torn down and a small park was created, dedicated to the victims of the tragedy. At the center of the park is the cupola of the original building, the only part that has been preserved. At the entrance to the park is a bronze plaque that contains the names of all the children who were killed on that terrible day.

The parents of those children survived the massacre, but their lives were never the same again. Some of them moved away from Bath in the years that followed, but it’s unlikely they ever really escaped their horrible memories. For those who stayed behind, the bloody history of that day was always present and to many people, the community remains a place where death came calling on what should have been a beautiful spring day. Instead, it became the day when the twisted obsessions of a dangerous man claimed the lives of dozens of innocent people and forever stained the landscape of rural Michigan.

GHOSTS OF THE MASSACRE

With a horrific event such as the Bath School Massacre, it’s no surprise that ghostly tales and legends have sprung up around the scene of the disaster. According to stories, people claim to have had many experiences at the park where the two schools once stood. Voices are heard, as well as cries for help, and recordings have been obtained that allegedly contain the eerie voices of the lost, still seeking help after decades have passed. Unexplained cold spots are also felt -- as well as the strange touch of unseen hands, as if they are reaching out from beyond the grave.

And, according to first-hand accounts, the massacre site is not the only place in Bath that is haunted. A funeral home on Main Street, where many of the bodies of the victims were prepared for burial, was turned into an apartment house many years after the massacre. A tenant who moved into the place in 2000 began to experience odd happenings in the house, starting almost from the night she moved in. As she climbed into bed that night, she felt the unsettling stare of someone watching her -- and things were never the same after that.

She began hearing footsteps going up and down stairs that had been removed years before and voices coming from the basement. Toilets flushed by themselves, water faucets turned on and off and she claimed to hear the sobbing and crying of children. When she heard the sound of breaking glass one night, she called the police. Officers came to search the house but when she unlocked the basement door, both men refused to go down and look around. When the landlord came to her the following day and blamed her for damage that had been done in the basement, she showed him the police report and he was as puzzled by the disturbance as she had been.

A short time later, she began seeing the ghosts.

The first victim she saw said that his name was George Hall and that he had been eight years old when he died at the school. According to the witness, George’s ghost had no legs. The spirit, she claimed, was a prankster and loved the tenant’s cat, along with other animals. There was also a little girl, who was missing a hand and wanted the tenant to look for it. The spirit told her that she had been wearing a ring that was special to her when she died at the school and the ring was still on one of her missing fingers.

During the time she lived in the house, the tenant stated that the ghostly occupants were always nearby and seemed to need something from her -- something that she seemed to be unable to give. They wanted help, she said, but she didn’t know how to help them. For reasons that she couldn’t understand, the children were unable to rest.

And one has to wonder if they still linger there, unable to find peace after their terrible deaths, still searching for solace and understanding of the bitter crime that took them from this earth.